- March 13, 2019

g.U.s & EU-IOUs

- by David Schildknecht

Until now, Germany’s efforts at conforming to a framework for EU-wide Wine Law ratified in 2008 have been merely pro forma. But an officially sanctioned “transitional” phase of accommodation has come to an end, and serious reckoning is due. How rapidly changes come to the manner in which German wines and vineyards are named and categorized, to what degree, and with what consequences for winegrowers and consumers remains to be seen. The experiences of three pioneers who have grasped at opportunities afforded by the new EU Wine Law offer an excellent jumping-off point for considering those questions. (Bungee cords, blindfolds, or parachutes are not options.)

Until now, Germany’s efforts at conforming to a framework for EU-wide Wine Law ratified in 2008 have been merely pro forma. But an officially sanctioned “transitional” phase of accommodation has come to an end, and serious reckoning is due. How rapidly changes come to the manner in which German wines and vineyards are named and categorized, to what degree, and with what consequences for winegrowers and consumers remains to be seen. The experiences of three pioneers who have grasped at opportunities afforded by the new EU Wine Law offer an excellent jumping-off point for considering those questions. (Bungee cords, blindfolds, or parachutes are not options.)

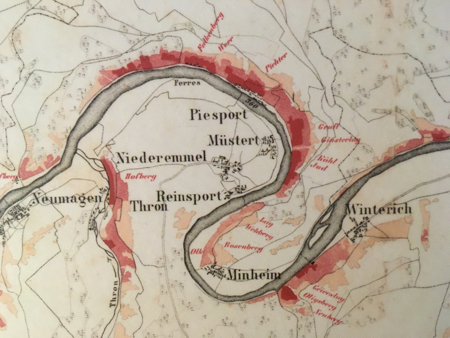

To the right: Prussian Tax Controller Franz Josef Clotten’s influential early exemplar of statistical cartography (1868), graphically depicting the perceived return value on various vineyard sites on the Saar and Mosel, including in Dhron (“Thron”). Below: Winegrower Andreas Adam measures must weights in various Dhron vineyards to help decide which will be his first-harvested in record-early vintage 2018. Whatever possessed otherwise sensible people to imagine Clotten and Adam being engaged in a common endeavor as “classifiers”?

Greener Grass and Spurious Dichotomies

Greener Grass and Spurious Dichotomies

“The grass is always greener on the other side of the fence.” So goes an expression Anglophones only ever utter tongue-in-cheek. And as I have often pointed out since late in the last millennium, there is more than a little irony in the fact that movers and shakers in the German and Austrian wine realm have been expressing increasing admiration, at times bordering on veneration, for what they like to call the “Romantic” or “Romance” system of wine “classification”—and corresponding distain for the “Germanic” system under which they have allegedly chafed for the past fifty (according to some, eighty) years—during precisely the same period when France’s regimen of appellation d’origine contrôlée (AOC), or “protected designation of origin,” has come under internal attack both from winegrowers who perceive its ever-extending and entangled tentacles as strangulating, and from those who conceive of varietal labeling as a commercial panacea.

That self-styled “Romantics” in Germany are trading in a spurious dilemma and in their Manichean zeal often misrepresent both the classificatory regimens they propose to take as models and that which they despise, not to mention adopt an uncritical view of the formers’ limitations while overlooking their frequently unfortunate unintended consequences, are claims I have previously defended at length1 and don’t propose to readdress in any detail on this occasion. (With respect to the VDP’s romantic misrepresentation of Burgundian reality, consult the appropriate section of a lengthy earlier article that I published on this site.) Suffice it to note here that Germany’s 1971 Wine law most definitely—albeit inadequately—addresses place of origin; whilst France’s AOCs, like nearly all traditional wine appellations, are very much concerned—albeit not, like Germany’s 1971 Wine Law, obsessed—with setting minimum must weights. (That must weight might become a wholly inadequate proxy for ripeness has only dawned on growers over the last several decades in the sign of global warming.)

Romantics have certainly felt encouraged, if not ready to declare victory in their perceived contest of ideologies, by Germany’s 21st-century commitment, shared by all EU member states, to organize wine classification and labeling under a common system and with shared or at least precisely parallel nomenclature—since the system in question is explicitly patterned on France’s familiar regimen of appellation. (I’m using “familiar” here in the sense of notoriety, not that of being widely well understood) This includes express fealty to the dictum: “The narrower the place of origin, the higher the quality.” Having recently dealt at length with this slogan—false if a purported statement of fact; ludicrous if interpreted as an aesthetic or moral principle; arbitrary and high-handed if a diktat—I shall limit myself here to pointing out that in the context of wine law it is categorically out of place. (Update Feb. 16, 2022: Germany’s new Wine Law purports to adopt this slogan as its guiding principle and the solution to a “problem”!) Wine law can set stricter—i.e., more onerous or costly-to-meet—standards for categories of wine the narrower the vine surface area to which they apply. It can even insist—and in France sometimes does—on dubbing certain vineyards “grand cru,” others “premier cru,” and yet others neither. But wine law makes itself look ridiculous if it claims to establish that wine of one sort is inherently higher in quality than that of another. If “higher in quality” means “tastes better,” one recognizes this ridiculousness right away; and insofar as “higher in quality” means “commands a higher price,” that is obviously for the market to decide or, as was the case in 19th-century Prussia, for the taxman to take covetous note.

The inference that wine legislators are in the business of passing qualitative judgements also infects much of the critique leveled at Germany’s 1971 Wine Law. To take one thoroughly typical example, I really cannot understand what Stuart Pigott has in mind when he writes: “Ever since the Wine Law of 1971 [went into effect] the sugar content of grapes (technical term: must weight in degrees Oechsle) has been the factor [entscheidende Faktor] that determines the qualitative ranking of every German wine.” Where is this written in that Law? It has certainly never been true in practice. The only terminology on any German wine’s label that relates to must weight is the Qualitätswein imprimatur itself and the so-called Prädikate, whose utilization the law leaves entirely optional, merely setting a minimum must weight for each. If a grower charges more for any given wine that he or she labels as Auslese than for a corresponding Spätlese—and that is not always the case—this reflects many factors other than must weight. German Wine Law takes no stand on whether a wine labeled “Piesporter Michelsberg Kerner Auslese” is perforce superior or inferior to one labeled “Piesporter Goldtröpfchen Riesling Spätlese.” And the market will almost certainly reward the latter with a higher price. I don’t defend—indeed, have long decried—what I call the German Wine Law’s “oeschlemaniacal” obsession with must weight. Nor do I endorse its usurpation of the once-approbative term “Kabinett” or the once descriptive terms “Spätlese” and “Auslese.” But German Wine Law does not stipulate that “higher Prädikat” means “higher quality.”

Given the aforementioned popular misperceptions, it isn’t surprising that breathless enthusiasm has greeted the recent approval of five g.U.s (geschützte Ursprungsbezeichnungen—a.k.a. Protected Designations of Origin, or PDOs for short) applicable to German wine. These represent the first of their kind more specific than thirteen that are eponymous with Germany’s wine regions (and whose registration represented Germany’s minimum requisite commitment to the new EU system). Under the title “Provenance is Decisive” (Herkunft Entscheidet), Stuart Pigott, writing in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, greeted the May 2017 accession of Bürgstadter Berg in Franken to g.U. status as “the breaking of a new day [Zeitalter] for German wine,” while a just-published article by Jean Fisch and David Rayer in their journal Mosel Fine Wines treats three newly approved g.U.s covering the official single vineyard, or Einzellage, Winninger Uhlen under the heading “A New Era for German Wine?” and appears to affirmatively answer that question by alleging: “the registration of the[se] Uhlen gUs represents a quiet revolution for German wine.” In what follows, I shall attempt to place these five g.U.s in the context of current German law and practice and to assess the possible future significance of g.U.s, as well as some potential pitfalls inherent in their establishment and implementation.

Protection or Proaction?

From January 1, 2019, the Schutzgemeinschaft Mosel (“Mosel Protection Committee”)—for which there is a counterpart in each German growing region, intended to assume a role similar to that of France’s long-standing comitées interprofessionelles or of Austria’s regional Weinkomitees—will serve as an official advisory body to review applications for g.U. status. A Schutzgemeinschaft cannot deny or approve such applications, but will forward them to the BLE (Germany’s Federal Agency for Agriculture and Food) with a recommendation that they be submitted for approval by EU authorities—or not. (As a g.U. receives approval, it will be added to an EU registry appropriately named E-Bacchus. Technically, the odd couple of Mosel and Mittelrhein form a single Schutzgemeinschaft, but I am ignoring that in what follows.) Registration of Gewannnamen (or official place-names on the cadastre) will continue to be the provenance of each relevant German State (Land), but, as will shortly become clear, it seems highly unlikely that the Schutzgemeinschaften will be able to avoid taking a position on such applications as well.

Each regional Schutzgemeinschaft draws its representative delegates—who are elected at an open meeting—from among winegrowers as well as shippers and cooperatives. (In the case of the Schutzgemeinschaft Mosel, there are respectively 12, 6, and 2 representatives each from those three categories.) As will become clear on a bit of reflection (or certainly to anyone who manages to digest the entirety of this text), in order for the sometimes conflicting interests of growers, shippers, co-ops, and grower organizations, like the VDP—not to mention the diverse structures currently operative at State-, Federal- and EU-level—to be effectively reconciled would require these Schutzgemeinschaften to become highly proactive and to agree on a common set of criteria governing such thorny and inevitably contentions matters as what justifies a given vine surface area being mentioned by name, a question to which Germany’s 1971 lawgivers manifestly gave at best superficial and inadequate attention and which today’s VDP has sidestepped with pleonastic pronouncements—but then, as a grower organization, the VDP’s primary concern is, understandably, to meet the needs of its members, including as regards what discrete vine surface areas should be deemed worthy of mention. There are really four competing structures impinging on German nomenclature, classification, and regulation as it pertains to wine and vineyards: that of Germany’s astonishingly resilient albeit almost universally decried Wine Law of 1971 (regularly revised, but until now only in detail); that imposed by individual German States (Länder); that of the highly influential VDP; and that dictated by EU law.

Those sponsors of specific g.U.s and members of the new Schutzgemeinschaften with whom I have recently corresponded concur that it is too early to know how much authority the latter will exercise in practice, let alone whether they will be able to set intra-regional and coordinate inter-regional standards governing vineyard designation, to say nothing of countless other intimately related practices, all of which are to be incorporated into Lastenhefte (“product specification books”) for the maintenance of which the Schutzgemeinschaften will become responsible. Dirk Richter of Weingut Max Ferd. Richter—a veteran Mosel estate owner who has been intensively involved with the legislation establishing Schutzgemeinschaften but sits on the Schutzgemeinschaft Mosel in his capacity as a shipper—wrote me to suggest that since bottling-growers, bulk producers, shippers, and co-op members all have to be consulted in the course of arriving at any decisions, “in my opinion this precludes any earth-shaking [umwerfend] let alone revolutionary accommodation to an ambitious [new] system of appellation of origin [Herkunftssystem].” Instead, he predicts, “one will have to begin by taking small steps in consensus and then see how things develop.”

Fudge and Friction

In what can only be called EU-typical fashion, friction among the various frameworks that currently impinge on German wine practices has up to now largely been lubricated using fudge. As already intimated, existing categories stipulated by Germany’s Wine Law are formally brought under the EU-stipulated umbrella of geschützte Ursprungsbezeichnung only insofar as each of Germany’s growing regions has been assigned an eponymous g.U., with any further details yet to be worked out. As Gerd Knebel—head of the Weinbauverband Mosel (the official lobbying association for Mosel wine producers ) and long-time editor of the leading intra-professional journal called Winzer-Zeitschrift (aka DWZ)—has noted in the course of attempting to persuade his largely reluctant fellow vintners that regulatory reform is an urgent necessity: “Many winegrowers appear not yet to have noticed that they no longer bottle any QbA wines, but rather, since the EU Wine Marketing Reform of 2009, only German Qualitätsweine mit geschützten Ursprungsbezeichung.” Such obliviousness is hardly surprising. A look at the “product specifications” governing “g.U. Mosel” make clear that they essentially redeliver the criteria and categories formerly associated with QbA—merely worded in an acceptably “romantic” way.

The VDP has attempted to absorb or neutralize the impact of potentially significant State regulations, notable examples being the 1999 recognition by Hessen of “Erstes Gewächs” and more recently as well as importantly provisions in Rheinland-Pfalz (subsequently also in other German Länder) for registering Gewannnamen (cadastre names). The VDP views its “pyramidic” classificatory structure as inherently consistent with the system that inspired it, namely, Burgundy’s labeling regulations, and since those regulations form a part of French appellation law, the VDP’s classificatory structure must surely (so it’s imagined) be in sympathy if not already consistent with EU demands. Confidence is thus exuded that any tectonic wrinkles can be worked out.

But one is entitled to skepticism that pressure to conform to EU regulations will result in any clear, uniform set of rules and practices governing German wine. This would represent an enormous task of untangling convoluted strands of vineyard classification and wine categorization and reconciling divergent interests among the many parties involved. And when it comes to clarity and consumer-intelligibility, the track record of those institutions involved— most conspicuously Federal lawgivers and the VDP—is hardly encouraging. Nor do I need to inform readers that resentment of EU bureaucracy and strictures is widespread among citizens of member States, surely including a significant share of German vintners, notwithstanding their nation’s nominal embrace of a French model when it comes to wine (unlike in matters fiscal or economic).

Upon reading an article in Mosel Fine Wines about the introduction of German wine g.U.s, Calgary wine merchant Al Drinkle suggested that “[a]t the very least, it adds confusion to a category that's already sufficiently tangled.” I suspect that beyond the confines of diehard “Romantics,” most lovers of German wine will share Drinkle’s concern. When I asked Reinhard Löwenstein , a g.U. pioneer and member of the VDP’s six-person steering committee, “Don’t you think, given the already existing layers of German wine nomenclature—Gewann; Einzellage; VDP-Erste and -Grosse Lage; EU g.U.—that without clear guidelines, meticulous planning, prejudice-free coordination, and consequential execution a Babel-like chaos will ensue?” I could hear him laughing as I read his reply. “In a word, yes, although I would take issue with your formulating that in the conjunctive [i.e., my having written ‘will’]. It’s a fact that bezeichnungsrechtliche Chaos has already ensued during the present transitional period.” (Bezeichnungsrecht is literally the law concerning how things—in this instance, wines—get named.) “But we live in a democracy,” adds Löwenstein. “A new wine law by fiat [“ex mufti”—only Löwenstein would think to use that expression] is unrealizable. And you have experienced yourself how difficult it is even for the professed avant garde, namely the VDP, to orchestrate a sensible model as a private initiative. So the question is, do we wait until all branches [of the wine trade] have been convinced; or do we take small steps in the right direction? I chose the latter path.”

This 1901 tax map of Nahe vineyards rates the original Frühlingsplätzchen, Auf der Lay, and Halenberg as among Monzingen’s top(-taxed) sites. They still are. But in 1971, the name "Frühlingsplätzchen" was co-opted as an official "Einzellage" incorporating everything left and right of the village other than Halenberg. To remedy that situation, Werner and Frank Schönleber made use of 2014 legislation in Rheinland-Pfalz to register the Gewanne Auf der Lay; then spearheaded an effort that, in 2018, saw the entire range of south-southwest-facing slopes east of town (everything from Palmenstich to Hungerberg on the above map) registered as the g.U. Monzinger Niederberg.

This 1901 tax map of Nahe vineyards rates the original Frühlingsplätzchen, Auf der Lay, and Halenberg as among Monzingen’s top(-taxed) sites. They still are. But in 1971, the name "Frühlingsplätzchen" was co-opted as an official "Einzellage" incorporating everything left and right of the village other than Halenberg. To remedy that situation, Werner and Frank Schönleber made use of 2014 legislation in Rheinland-Pfalz to register the Gewanne Auf der Lay; then spearheaded an effort that, in 2018, saw the entire range of south-southwest-facing slopes east of town (everything from Palmenstich to Hungerberg on the above map) registered as the g.U. Monzinger Niederberg.

Test cases in Franken and the Nahe

Bürgstadter Berg

Both the Fürsts in Franconia’s Mainviereck sector and the Schönlebers in Monzingen on the Nahe—whose estates surely figure on most German wine critics’ lists of that country’s top dozen—had entirely sensible justifications for their g.U. applications and were able to enlist the support of numerous fellow-growers from their respective communities in lobbying for the establishment of local g.U.s. But the extent to and ways in which those g.U. designations will be employed remains uncertain, as well as subject to potential ambiguity and confusion.

In the Fürsts’ case, the traditional referent “Bürgstadter Berg” was revived for a surface area that prior to 2010 was coextensive with that of the 52 hectare Einzellage Centgrafenberg, so at first blush one might wonder why register another, less prestigious name? The explanation lies in subsequent developments, as well as in VDP- and Fürst-internal classification. In 2010, at Fürst’s prompting and with the support of his fellow-growers, a new 11-hectare Einzellage, Bürgstadter Hundsrück, was federally recognized, carved-out from the Einzellage Centgrafenberg. And of the roughly 42 hectares that remain Centgrafenberg by German Wine Law, the VDP considers only 28 hectares worthy of declaring as “Centgrafenberg,” i.e. as representing a VDP-Grosse Lage. Given that background, it becomes clear why Sebastian Fürst says that “from the beginning the idea [behind a g.U. Bürgstadter Berg] was to establish a lovely, geographically delimited ‘premier cru’.” This endeavor was thus a response to the VDP’s stipulation (applicable in most regions, including Franken) that there be “Erste Lage” wines higher than “Ortsweine” (“village wines”) and lower than wines from “Grosse Lagen” (“top sites”) in that organization’s classificatory “pyramid.”

“The VDP classification is what matters [whereas] the g.U. plays next to no role in our communication,” explains Fürst. “We just needed currently to employ that tool to enable the use of our [chosen] site name.” He adds, of the VDP classificatory categories: “I don’t consider mixing [these] up with Gewannen, Einzellagen etc. expedient.” One can certainly sympathize with his desire not to muddle the VDP classification. But a revision, revocation, or reconciliation must begin to take place of the “old” wine law with its Grosslagen and Einzellagen (not to mention Prädikate), as well as of the provisions for registering Gewannnamen, with the system to which EU member States have now committed. And it would be a shame if the VDP’s influential classificatory system, employed as it is by a majority of Germany’s most prestigious estates (and imitated by many nonmembers), could not be incorporated into that process. (Apropos the choice of g.U. as tool and the “mixing up” of classificatory categories, it should be noted that in some instances, a VDP member has been permitted to choose the name of his or her VDP-classified vineyard holding from outside either the roster of Einzellagen or Gewanne and without applying for g.U. status. For example, Lauer’s [Ayler] Kupp “Stirn” employs a local descriptor for the upper section of the Gewann “Im untersten Berg”—while Kupp “Unterstenberg” is separately VDP-classified.)

That the specifications for the new g.U. Bürgstadter Berg reflect every conceivable style, Prädikat, and grape variety (to my surprise, even including Zweigelt) that might be associated with contemporary Mainviereck viticulture, certainly suggests an invitation to widespread utilization. Not being members of the VDP, though, other local growers who supported this g.U.’s establishment may perceive it or utilize its name somewhat differently than does Fürst. Meanwhile, if one consults the VDP’s vineyard website, what appears as Bürgstadter Berg will reflect Fürst’s usage: not as a surface area coextensive with the eponymous g.U., but rather as the surface area consisting of the Einzellage Centgrafenberg minus its VDP-Grosse Lage portion. (If you needed to re-read these last three paragraph, then I trust I shall have made my point concerning potential ambiguity and confusion.)

Monzinger Niederberg

The primary Monzingen vineyard hillsides stretch for nearly a mile on either side of that village, with a substantial, low-lying gap in between, occupied with buildings and infrastructure. Just east of town lies the prestigious 8.5-hectare Einzellage Halenberg. The highly heterogeneous, 65-hectare Einzellage Frühlingsplätzchen is located primarily west of town, but also picks up again on the other side of Monzingen, wrapping most of the way around the Halenberg, then continuing for half a mile further downstream.

The idea behind g.U. Monzinger Niederberg was to register a name long used to refer collectively to the slopes east of town and thereby address the worst of Frühlingsplätzchen’s ambiguity, since that Einzellage’s eastern portion is not only geographically but also geologically and microclimatically quite distinct from the larger portion to the west, which (as illustrated on the 1901 tax map excerpted above) incorporates the vineyard that was known as Frühlingsplätzchen prior to 1971. It remains to be seen, though, how many growers will utilize the name “Niederberg” on labels. Frank Schönleber says that he intends to do so pending the VDP’s approval of it as an official VDP-Erste Lage (update Feb. 16, 2022: with vintage 2019, that has come about), although some of what the Schönlebers harvest from this surface area will continue to be incorporated into a generic (Gutswein) or village-designated (Ortswein) bottling. Meantime, any grower bottling wine from the eastern portion of the Frühlingsplätzchen Einzellage can henceforth choose between “Frühlingsplätzchen” and “Niederberg.” Or, in principle, he or she could still register any Gewannname that applies within this surface area. "At the end of the day,” declares Schönleber, “it doesn't matter to me whether Einzellage, Gewannname, or g.U. gets used. What's important is that a wine's place of origin is clearly defined, and, if possible, also sensorially confirmable."

The new g.U.s initiated by Fürst and Schönleber thus make eminent sense, and by no means solely from the standpoint of the VDP’s classificatory model; though, as Fürst explains, “we encourage our colleagues in town to take the VDP classification as their model, and those who do so have had success.” It makes perfect sense, for example, to speak of Bürgstadter Berg as encompassing both the Einzellage Hundsrück and the VDP-Grosse Lage Centgrafenberg. But the choice of a g.U. as, in Fürst’s expression, the chosen “tool,” was predicated on recognition that g.U.s both represent the building blocks and reflect the structure intended to apply in future to wine law throughout the EU. Had he wished, Fürst could instead have sought approval for yet another new Einzellage, or for a VDP-Erste Lage recognized solely by that organization, in either case consisting of the present Einzellage Centgrafenberg minus the portion of it that is classified as an eponymous VDP-Grosse Lage.

On this panoramic photo, Reinhard Löwenstein marked the position of what eventually became his diminutive g.U. Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay. A portion of the far larger g.U. Uhlen Laubach is visible to its left. With apparent perversity, as explained further below, the aggregate surface area of three Gewanne whose names incorporate “Blaufüsser Lay”—Ober der Blaufüsser Lay, Auf der Blaufüsser Lay, and Unter der Blaufüsser Lay—was assigned by Löwenstein largely to the g.U. Uhlen Laubach and represents the portion of that g.U. depicted front and center in this photo.

Test Case Winninger Uhlen

However self-interested they may have been from a marketing standpoint, Reinhard Löwenstein’s motivations in inaugurating an appeal for tripartite g.U. status within a portion of the Winninger Uhlen were literally if not figuratively rock solid. As Lars, following up on the many historical and geological observations of Joachim Krieger, has elsewhere explained, Uhlen might not be huge by the standards of Germany’s Einzellagen, nor was the surface area traditionally referred to as “Uhlen” inordinately enlarged by the 1971 Law that created those Einzellagen. Nevertheless, the long arc of steep, terraced vineyards that hugs the Mosel’s Left Bank just upstream from Koblenz (and extends across a communal boundary into Kobern) incorporates three very different variations on Mosel slate, whose profoundly distinctive influences on Riesling have for years been deliciously charted by Löwenstein in three different bottlings, which he sometimes identified on their labels by means of an initial—“B,” “L,” or “R”—and sometimes via the circumlocution “Schieferformation x,” where x stood for one of the three names for which he eventually secured g.U. status. The g.U. Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay is on a sand-rich variant of the Mosel’s familiar blue Tonschiefer (clayey slate); Uhlen Roth Lay, as its name suggests, on a red variant, rich in quartzite, iron oxide, and magnesium; while Uhlen Laubach refers to a specific geological formation comprising gray slate with (for the Mosel rare) fossiliferous limestone. (Tremendous geological detail as well as evocative, at times downright poetic explications and evocations of the Uhlen can be found in the brochure published in 2013 by Weingut Heymann Löwenstein, in collaboration with geologist Dr. Ralf Kröll and wine journalist Stuart Pigott.)

Any Winningen grower with holdings in the relevant portions of Uhlen and willing to abide by the substantial additional criteria stipulated for the three new Uhlen g.U.s, is free to label his or her wines accordingly. Löwenstein’s fellow-VDP grower Matthias Knebel, for instance (who just happens to be the aforementioned Gerd Knebel’s nephew), will now be able, if he wishes, to label wines as “Uhlen Roth Lay” or “Uhlen Laubach,” which he, too, had previously alluded to using the initials “R” and “L.”

A peculiarity (some might claim perversity) of Löwenstein’s g.U. Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay lies in the fact that most of the surface area traditionally referred to by that name—and divided in the cadastre into Gewanne: Ober der Blaufüsser Lay, Auf der Blaufüsser Lay, and Unter der Blaufüsser Lay—is allocated not to the diminutive g.U. Blaufüsser Lay but instead to the g.U. Uhlen Laubach. This is explained by Löwenstein’s account of how he utilized the freedom in choice of name permitted under g.U regulations:

With the g.U.s in Uhlen, I was absolutely not being guided by Gewannnamen, but, rather, by taste and geology, respectively. The so-often and fondly cited “old Gewannnamen” from the time before 1971 frequently have nothing to do with terroir. Naturally, it was appropriate to have found an old term [i.e., “Blaufüsser Lay”] that not only coincided with a portion of several Gewannnamen but additionally incorporated “blue,” which describes the slate at this spot. The situation with Roth Lay is similar: While no particular parcel is so named, it refers to the reddish rock outcropping above the vineyards. Only in the case of Laubach was I unable to find an extant local referent, so I had to call upon official geology.

The so-called Laubach Formation, namely, with its rare combination of slate and calcaire, undergirds most of those three Gewanne that incorporate the name “Blaufüsser Lay.” (Incidentally, this geological formation also crosses the Rhine, at a dark-red fleck on the 1904 Prussian tax map signifying a vineyard that was farmed for centuries by Carthusian monks but nowadays represents a few largely built-up blocks of suburban Koblenz. (I know this from having sought out the spot in subsequently disappointed anticipation.)

I asked Löwenstein whether he thought that the existence of his g.U. "Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay" would preclude a grower in future registering any of three Gewannnamen that share the same geographical referent: Auf der Blaufüsser Lay, Unter der Blaufüsser Lay, and Ober der Blaufüsser Lay. “I would assume so,” he replied, adding “I think any court would say that this represented risk of confusion.” A plausible enough view—but also an intimation of how messy and contentious the layering of wine nomenclature might in future become. Gerd Knebel explains that this is the sort of conflict that the Schutzgemeinschaft Mosel would in future address, presumably by declining to advocate for the registration of names that invited confusion. But he adds that one can, at best, merely speculate as to whether a Schutzgemeinschaft Mosel, had it existed at the time, would have looked with favor on Reinhard Löwenstein’s application for tripartite Uhlen g.U. status or, in particular, his utilization of “Blaufüsser Lay”

Given Löwenstein’s explanation, readers will not be surprised to learn that he thinks in future “a clear demand must be made to forbid [the utilization of] Gewannnamen in their current form. They convey the impression of referring to a terroir that often doesn’t exist. Whoever wants to do something [along these lines] in the future should apply for a g.U. In that case, the State Geological Office will be involved and things can proceed in a rational manner.” Indeed, the provision instituted in 2014 whereby growers in Rheinland-Pfalz may register Gewannnamen and utilize these on their labels in no way concerns itself with site character. But it does de facto create a grower’s right to reference the boundaries and names of surface areas as they appear in the cadastre. So the potential for conflict or confusion is obvious. (Confusion vis-à-vis Einzellagen already exists, given that prominent growers—largely for VDP-internal purposes—have registered and are utilizing such Gewannnamen as Im Hahn, Im Pittersberg, and In der Kirschheck alongside the not-quite-eponymous Einzellagen Hahn, Pittersberg, and Kirschheck. VDP-President Steffen Christmann has recently even registered the Gewannname “Meerspinne” notwithstanding there still being, alas, an eponymous Grosslage.)

As I reminded Löwenstein, the aforementioned 2014 provision was greeted with widespread enthusiasm, including by the VDP, as offering a way out of the dilemmas and dead ends presented by Germany’s official Einzellagen, whose establishment routinely ran roughshod over geological, topographical, and micro-climatic considerations. Moreover, wouldn’t a ban on future registration of Gewannnamen represent shutting the barn door after the cows have gotten out (or trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube)? Not as Löwenstein sees it. "So far, the Gewannnamen haven't done any great harm, so better to quit now than wait. As for [their endorsement by] the VDP, here, fortunately, Gewannnamen may only be utilized subject to geological vetting." The count in Rheinland-Pfalz is already up to 238 registrations of place-names (update: as of March 2021, 301), a substantial portion of these instigated by VDP members, although a significant share of that total has yet to actually be utilized on any label.

Surely, though, traditional place-names ought to be accorded respect regardless of their geological relevance or irrelevance. That Germany’s 1971 Wine Law played fast-and-loose with them in the establishment of official Einzellagen is rightly among the many charges to have been brought against it. “Zeltinger Schlossberg,” for example, was not only an appellation of long-standing prestige but also referenced an enormous castle whose remains are still a landmark today. So, not to put too fine a point on it, co-opting that name for the hillside behind the village of Zeltingen and re-dubbing Schlossberg “Zeltinger Sonnenuhr” constituted fraud. Apropos Einzellagen, Löwenstein believes that many of these—including most of the best-known along the Mosel—should become the basis of future g.U.s “provided Germany wishes to implement EU-standards correctly.” But, unsurprisingly, he adds that “they need to be vetted for geological-microclimatic homogeneity and [correspondingly] corrected,” which would certainly require the implementation of guidelines more adequate and transparent than those employed by the lawgiver in 1971 or the contemporary VDP. And, as if agreeing on such standards would not be tricky enough, Löwenstein has incorporated into his three g.U.s stipulations much farther reaching than just those of geological and microclimatic homogeneity:

According to the EU-ordinance, all products should carry an indication of provenance [Herkunft]. And this should be defined, first geologically, but over and beyond that in terms of the “human” factor. A Bresse hen [for example] doesn’t just have to come from Bresse if it is to be called that, but must also be fed according to specified standards. A wine on whose label “Brauneberger Juffer” is inscribed should not just come from the eponymous site, but over and above that meet certain criteria, which have yet to be spelled out. The historic novelty of the new Uhlen g.U.s is that here for the first time this has been done; that for the first time the name of a wine from a single vineyard is bound by strict regulations and specifications. For example: Riesling; with a minimum of 7,000 vines per hectare; a maximum of 7,000 liters per hectare of cadastre surface— which [in the Lower Mosel’s steep, terraced slopes] equates to 50 hectoliters per hectare actual surface; a reasonably [einigermaßen] uniform taste profile [Geschmacksprofil] (no Kabinett, no Spätlese) etc.

That’s a lot to chew on conceptually. And, incidentally, Löwenstein’s “etc.” incorporates many additional criteria including such worthy restrictions as prohibitions on many must- or wine-“enhancing” additives and treatments that are otherwise permitted under German Wine Law. But before I attempt to attack his traditional conception of appellation with bared incisors and reduce it to bite-sized (if not necessarily digestible) pieces, it will be useful to review the overall conceptual landscape.

Einzellagen, Gewannnamen, and g.U.s: Fundamental and Structural Differences

Choices of Name

While the names of Einzellagen are legally fixed, growers who launch appeals for the recognition of a new Einzellage can choose the relevant place-name, which might be—or closely resemble—that of a Gewann (e.g., among recently created Einzellagen, Oestricher Rosengarten, authorized in 2013) or might instead harken back to some other traditional or even estate-internal place-name (e.g., Kiedricher Turmberg, 2005).

The names of Gewanne are also legally fixed, so an appeal to register one of these is perforce limited to the existing stock of names, and only a single name applies to any given spot.

A g.U., as we have already seen, can in principle take names of any sort, including such as already are or formerly were in use to refer to a particular area (e.g., Bürgstadter Berg or Monzinger Niederberg), such as refer to an identifying landmark (e.g., Roth Lay), such as allude to the names of nearby Gewanne (e.g., Blaufüsser Lay), or such as refer neither to a previously named surface area nor a landmark (such as, in the case of Laubach, referring to a geological formation). Until now, no g.U. has been coextensive with a single Gewann or Einzellage, but it’s not yet clear whether in future an application to receive g.U. status for a surface area coextensive with that of an Einzellage or a Gewann might be permitted to take the same name. For example, one way in which some observers, including many growers, imagine German Wine Law being assimilated into the new EU framework is for Einzellagen to be in effect redefined as g.U.s. (possibly with restrictions of the sorts that Löwenstein advocates and has applied to Winninger Uhlen).

Integrity of surface area and nesting

Both an Einzellage and a Gewann refer to a surface area that cannot overlap with that of another Einzellage or Gewann, a prohibition that includes the limiting but more significant case of one Einzellage or Gewann being located within the surface area of another. (Obviously, the surface areas of Gewanne lie within—and, in an extreme case, might be coextensive with— that of some Einzellage or other.)

By contrast, given that France’s AOCs (or, for that matter, Italy’s DOCs and DOCGs) are paradigmatic g.U.s, the geographical surface covered by one g.U. may overlap or be nested within that of another.

Non-geographical criteria

Einzellagen and Gewanne refer solely to the delimitation of a surface area. By contrast, as we have seen (and as all are familiar with from French appellations), a g.U. incorporates a wealth of additional detailed specifications including but not necessarily limited to acceptable grape varieties, must weights, alcohol levels, crop loads, viticultural practices, harvest practices, cellar practices, permitted additives, or applicable sub-nomenclature (such as that of Germany’s Prädikate) that is, in turn, subject to further criteria.

Before critically considering further implications of such non-geographical criteria, it is worth explicitly spelling out (even if you may say “that’s obvious!”) an overridingly important consequence of this feature of appellations when combined with that of overlapping or nesting: Any given vine surface area may, in principle, be subject to multiple g.U.s., as is the case throughout France, where the relevant appellation may depend on the grape variety being grown (a plot that yields AOC Saumur if planted to Chenin might be AOC Saumur-Champigny if planted to Cabernet Franc); condition of grapes at harvest (Chenin in a given plot might be appellated Anjou or, if picked in nobly rotten state, at a sufficiently high must weight and low yields, be appellated as Coteaux du Layon); wine-making (if grown in certain places and with certain yields, grapes qualifying as Muscadet de Sèvre et Main Sur Lie might be aged for the requisite period to classify under one of the recently instituted crus communales, such as Clisson); or on winery-internal criteria (a grower might choose to “declassify” his or her Vosne Romanée 1er Cru Chaumes to village Vosne Romanée, or Echézeaux to Vosne Romanée 1er Cru).

There is no way of telling whether German legislation—outside of that which treats each growing region as a g.U.—will in fact evolve to include geographically nested or overlapping g.U.s or multiple g.U.s applicable to a given surface area depending on what grapes are grown there, what techniques are followed, etc. But the very possibility alone should give pause, especially to anyone wishing to claim—as Fisch and Rayer do in their aforementioned account of Uhlen g.U.s—that g.U.s “add clarity” and will result in “consumer-friendly labeling.” In fact, as I shall shortly argue, there are additional reasons for considering such claims downright preposterous.

The Spector of “Appellationism”

Despite good intentions, there is a clear risk that minting g.U.s will contribute to what I have been decrying for years as “appellationism.”2 I have in mind an ideology that results in ever-expanding regulation in the ostensible interests of protecting quality; promoting the importance of place; and helping consumers make informed choices, while in fact resulting in creeping infringements on the rights and liberty of winegrowers; labeling so convoluted and layering of geographical and stylistic ranges so opaquely dense as to render consumers utterly confused; and, not least, paradoxically, in making it harder rather than easier, to discern the place from which any given wine originates.

Anyone skeptical of the just-alleged paradox need only consider a couple of Europe-wide trends.

First, growers unhappy with the technical and stylistic specifications connected with appellations of origin or confounded by the standards of “typicity” reflected in tasting panels empowered to grant or withhold those appellations, increasingly default to registering their wines merely as “vin de France,” “Wein aus Österreich,” or their equivalents, thereby ceding the right to supply on their labels a vineyard name or even any hint about where a given wine grew, save to the extent that their winery address might supply one. (And, in France—in whose Loire region the aforementioned trend threatens to reach epidemic proportions—even the employment of village names as part of an estate’s address is being forbidden, with only a postal code allowed). The consumer is thus confronted with an ever-growing array of wines identifiable solely by grower and fantasy name. Ironically, it is often growers exceptionally concerned to promote healthy soils and vineyard environments as well as to channel site with the least interference who find themselves compelled to resort to geographical anonymity and the employment of fantasy names.

It already frequently happens that distinctively delicious wines are refused recognition as German Qualitätswein while mediocrities no more—indeed, likely a lot less—recognizably of their region or sector pass with flying colors. Now imagine if, to take Löwenstein’s example, the name “Brauneberger Juffer” were bound not just to myriad analytic and procedural criteria over and above those governing Qualitätswein but, what’s more, to an einheitliches Geschmacksbild (“uniform taste profile”). For that not to invite abuse would require strict oversight of the relevant tasting panels to root out superfluous stylistic bias and conflicts of interest, personal as well as wine-political, something that has conspicuously never been accomplished in France.

Secondly, an obsession with ranking vineyards increasingly leads grower organizations and lawgivers to pull up the ladders behind them, with only chosen vineyard or village designations being allowed, or even to voluntarily withhold geographical information out of zeal to imitate what they are convinced is Burgundy’s recipe for reputational enhancement. The former trend is exhibited in Chablis’s prohibition on lieu-dit designations or the stripped-down lists of vineyard names permissible within the various regional branches of the VDP, restrictions that further encourage—indeed, practically compel—proliferation of fantasy names (as explained in section 3.d. of a critique of “Grosses Gewächs” I published on this site). A prime example of the latter tendency is the VDP’s insistence on “pyramidic” labeling, and on rendering village names inconspicuous on labels of wines from allegedly “great” vineyard sites (notwithstanding the many “Schlossbergs,” “Herrenbergs,” and so forth spread all across the viticultural map of Germany).

Or consider a recent case from France. What does it mean in practice that Pic Saint- Loup has been accorded self-standing AOC status as one of numerous “Grands Vins du Languedoc”? It means that the former umbrella appellation “Coteaux du Languedoc” no longer appears in front of “Pic Saint- Loup” on labels. And what does that mean for consumers? That few of them will any longer have the remotest notion from where in France the wine so-labeled originates. And this is how the Languedoc proposes to achieve a well-deserved and desperately-needed reputational boost: by withholding its name from the region’s top wines?

Nor is voluntary withholding of information in the interest of imitating Burgundy confined to Europe. Many growers in Oregon’s Willamette Valley label only a single cuvée or pricing tier “Willamette Valley.” Entry-level wines frequently get labeled instead merely “Oregon” for their State of origin – a State that incorporates more than 30,000 vine acres in climates ranging from maritime to desert and separated from one another by up to 350 miles. Prestigious vineyard-designated wines are increasingly labeled solely for a more specific and obscure American Vititcultural Area, which might denote a village (e.g., “McMinnville”) or a geographical feature (broad or narrow, e.g., “Ribbon Ridge”). Growers have generated a qualitative pyramid, but at the expense of consumer clarity or ready geographical orientation, not to mention of more rapidly or firmly establishing “Willamette Valley” as a name to conjure with internationally (like “Napa Valley”).

Which label offers more clues about what sort of wine you are about to taste?

Which label offers more clues about what sort of wine you are about to taste?

Style and Site

That the majority of wine appellations place significant limitations on style as well as site is intended in theory to kill at least three birds with one stone. A consumer will not only learn where the wine originates but also what sort of a wine to encounter under that label—hence the notion of an einheitliches Geschmacksbild—and with some sort of quality guarantee on top of that. But it must be emphasized that trying to sneak “typicity” in under the rubric of terroir represents fallacious, slight-of-hand reasoning. That two or more wines are recognizably marked organoleptically by their place of origin—or, as Schönleber neatly put it, that place of origin is “sensorially confirmable”— does not imply that those wines share any particular set of organoleptic markers. The personalities or indeed physiognomies of siblings might be influenced by and traceable to their parents, without those personalities or physiognomies tipping-off an observer to the fact that they are siblings.3

German and Austrian proponents of the spurious “Roman[ce]”-“Germanic” dichotomy seem to also be among those most enthusiastically purporting consumer benefits to be derived from incorporating stylistic criteria into geographically defined appellations. You might think that precisely observers of the German wine scene—to say nothing of advocates for the Mosel—would have been weaned off of this approach by their experience with “Grosses Gewächs.” That category was introduced under the guise of vineyard classification but, in fact, defined a specific style of wine intended to become Germany’s luxury category. The friction here between site and style eventually engendered outright fission when those many Mosel members who justifiably consider Rieslings with significant residual sugar the apex of their production and the epitome of their sites objected. This pressured the VDP into in 2006 recognizing “Erste Lage” as an umbrella term (“einheitlicher Oberbegriff”) designating the top classificatory tier of vineyards independent of wine style. (The term was replaced six years later by “Grosse Lage”).

It’s hard for me to imagine of what “romantic” enthusiasts like Fisch and Rayer are dreaming when they claim:

The deployment of a gU logic [will] ensure more clarity on the taste profile of any wine [which] in turn, would lift the barrier of uncertainty with which a consumer is faced today in a shop somewhere in the world: Is this wine dry or not? Will it taste full-bodied or light-bodied? Providing clear taste guidelines can only boost sales. (Mosel Fine Wines Issue No 44 – January 2019 page 29)

Set aside for just one paragraph the matter of dryness or sweetness as well as the fact that those Uhlen g.U.s whose advent Fisch and Rayer are celebrating allow for wines of less than 18 or anywhere over 90 grams residual sugar (i.e., only wines of 18 to 89 grams are precluded). A wide range of permitted grape varieties alone—ranging from white to “black” in the case of g.U. Bürgstadter Berg—means that a given g.U. will, taken by itself, scarcely serve as a guide to how the resultant wine tastes. Of course, on the Mosel or the Mittelrhein where Riesling dominates among high-quality wines, legislative or advisory authorities such as the Schutzgemeinschaften might choose to disallow g.U.s that do not stipulate exclusive employment of Riesling. And Löwenstein clearly believes that “Riesling” should go without saying. But I suspect that Moselaner seriously committed to terroir-inflected Pinot Blanc and Pinot Noir would strenuously and with some justification object. Certainly there are many communes and even individual Einzellagen—especially in the Pfalz, but increasingly elsewhere—with an equal claim to fame as Riesling or Pinot sites.

France already offers the classic example of what results from attempts to conceive of appellation as a matter of both provenance and style. If a Chenin Blanc is labeled “Coteaux du Layon” or “Quarts de Chaume” then it is perforce nobly sweet; if labeled “Savennières” or “Roche aux Moines,” (with very rare exceptions) dry. So far, so good ... provided a consumer memorizes the relevant rules. But Chenin’s wonderful stylistic malleability—so like that of Riesling—results in many appellations quite rightly applying to wines with a seamless range from bone dry through nobly sweet, and to wines sparkling as well as still. And while terms like “sec,” “demi-sec” and “moelleux” are legally defined for certain Chenin-based appellations—most familiarly those of Vouvray and Montlouis—it isn’t incumbent on growers to utilize them; and, in fact, the trend in recent years has been to expunge them from labels, so that at most some winery-internal convention associating a given vineyard or fantasy name with wine exhibiting a certain degree of sweetness can serve to guide the consumer. (I should add that, despite what Fisch and Rayer would apparently predict, wines from leaders in their appellation like Chidaine and Bellivière—on whose labels you will find no taste indicators to accompany the inscriptions of appellation—are in such demand that it’s doubtful whether their proprietors even want to see sales boosted.)

If the conventions one would need to internalize in order to tell whether a Mosel Riesling was dry or sweet were even one-tenth as numerous as the region’s wine growing communes, not to mention as the Greater Mosel’s more than 500 extant Einzellagen, then—ambiguous, elastic, and ill-fitting though some of these terms are—use of “trocken,” “halbtrocken,” “feinherb,” and the Prädikate would surely offer greater guidance in practice.

The principle sites in Winningen as depicted in the first, 1897 edition of the Prussian tax map.

The principle sites in Winningen as depicted in the first, 1897 edition of the Prussian tax map.

Reimagining Winningen

Fisch and Rayer write of Löwenstein’s g.U.s that “their full beneficial impact will only be felt once all remaining vineyards from Winningen have gone through some gU status as well, and the old system dating from the law of 1971 will have been abandoned.” Let’s not even try to imagine that distant and head-spinning future or ask what can possibly be meant by “all remaining vineyards” in a context where how vineyards are to be individuated is precisely what’s at issue. Instead, let’s merely confine our attention to the two Winningen Einzellagen with the most established reputations, those same two recognized by the VDP as “Grosse Lagen,” namely, Uhlen and Röttgen.

Let’s assume that just a single g.U. were to be assigned, geographically coextensive with the Einzellage Röttgen—though here, too, if one took geological homogeneity as a serious citerion (as Löwenstein did and hopes others will do), it’s possible that a case could be made for multiple g.U.s. Löwenstein’s VDP colleague Matthias Knebel has managed—at least, in years when nature cooperates—to craft some superb Röttgen Kabinett and Spätlese. So even in a world where the Prädikats were banished from Germany’s Wine Law, or, at least, from Rieslings grown in Winningen, why on earth should Knebel acquiesce to a g.U. that forbids wines of between 18 and 89 grams residual sugar? Löwenstein himself might be convinced that Rieslings from Röttgen, given that site’s distinctive terroir, should be allowed a range of residual sugar far wider than is permitted under regulations governing the three Uhlen g.U.s. And if a wine like that which Knebel today bottles as Röttgen Riesling Kabinett were still allowed—even if sans Prädikat—then it would perforce be a wine of significantly lighter alcoholic body than would a dry Röttgen Riesling from higher must-weight grapes. For the relevant g.U. to inform a consumer of the wine’s sweetness or body—or even of its potential range of sweetness and body—would require that he or she had internalized these different criteria from one g.U. to another. And this is merely to consider a couple of criteria conspicuously contributory to taste, while setting aside whether a g.U. Röttgen would demand the same criteria as does Löwenstein’s trio in matters of planting density, yield, permitted treatments and additives, etc.

Nor are Löwenstein’s g.U.s sufficient for dealing with the surface area of the Uhlen Einzellage, since by design they apply to only a portion of it. So even if compliance with the criteria governing those g.U.s were one day to be made mandatory, there would need to be at least one additional g.U. to govern the rest of today’s Uhlen. For that matter, even if it were decreed that only the surface area covered by Löwenstein’s g.U.s would henceforth be considered Uhlen, surely a grower who wants to bottle a wine blended across multiple Uhlen g.U.s should be permitted to label that wine “Uhlen.” At minimum, then, an umbrella g.U. Uhlen would still be needed. Incidentally, Fisch and Rayer make a misleading suggestion that “growers with too little holdings in each of the three [g.U.] terroirs may decide to [declare] their produce as Winninger Uhlen until they accumulate enough vineyards.” Who says any given grower will want or can afford to expand in those sectors, let alone wish to utilize g.U. designations that (for now, at least) are entirely optional? In any case, expansion into the g.U. Blaufüsser Lay is hardly likely, since it covers less than a half hectare (precisely one acre)!

In our imaginary scenario, the only Winningen wines allowed to be labeled more specifically are ones grown either in some portion of today’s Röttgen or in a reduced Uhlen—not that this scenario is either wine-politically conceivable or a good idea. (In addition to Uhlen and Röttgen, Winningen currently incorporates Einzellagen named Brückstück, Domgarten, and Hamm. Knebel is trying to get a prime portion of Brückstück—colored dark red on the Prussian tax map—recognized as a VDP-Erste Lage Sternberg.) But even advocates of a reduced future range of vineyard designates (notably the VDP, and also Löwenstein himself) would agree that other wines grown in Winningen, or at least certain of these, ought to have “village-“ or Ortswein status, i.e., be allowed labeling as mere “Winninger.”

So under our minimalist scenario—featuring a radical VDP-style pruning of allowable vineyard designations but an insistence on geological homogeneity as a criterion for their applicability and on g.U. status for each—just to cover adequately the Rieslings of Winningen would require a minimum of six g.U.s, three of which (namely, the ones that already exist) would fall within the surface area of a fourth and fifth g.U.—namely, Uhlen tout court and Winningen—which, like whatever g.U. or g.U.s ended up applying to today’s Einzellage Röttgen, might have different stylistic criteria than those that apply to Uhlen Roth Lay, Laubach, and Blaufüsser Lay. (Okay, technically, you’d have seven g.U.s if one counts “Mosel” ... but at this point, is anybody counting? What about an additional g.U. Terrassenmosel?) This might all make sense—especially to the hierarchically- and pyramidically-minded, who heaven knows seem nowadays in the ascendance among German growers, bureaucrats, and wine critics. But would it be easier for a consumer to comprehend than is today’s notoriously confusing status quo? Eliminate Prädikats and taste designators—or retain them for just certain of the five or more site-specific Winningen g.U.s—and the consumer’s burden would only increase. Faced with just a label and the questions “dry or sweet?” “full-bodied or light?” how many consumers would have internalized the requisite conventions? Any in their right mind would instead look to the wine’s alcohol level as their most viable remaining (albeit far from perfect) guide.

Sancta simplicitas!

Sancta simplicitas!

Even given the complications applicable to France’s Chenin-dominated appellations—to stick with that example—a certain relative simplification is accomplished by having a given appellation apply not just to wines from the eponymous commune but also to those of others nearby. Vouvray, for example, can issue from any of seven communes; Montlouis across the river from three. But can you imagine, say, growers in Erden and Ürzig agreeing to use just one of those names; or growers in Zeltingen, Wehlen, and Graach agreeing henceforth to label their wines “Wehlen”? One might argue persuasively that Germany simply has many extended sub-regions in which a Burgundian level of specificity is justified; indeed neighboring German Riesling-growing villages or vineyards often display significantly greater geological and climatic disparity than do their counterparts in the Côte d’Or. Still, the romance of a Romance system is liable to wear thin on consumers once translated into hard-to-grasp reality, incorporating myriad sometimes nested or overlapping g.U.s for every village.

Certainly one can imagine many growers—especially within the VDP—advocating future German g.U.s stipulating Riesling that is either of legal Trockenheit and minimum 12% alcohol, or else nobly sweet, because those backing their introduction believe that these parameters reflect the traditions of their region and or best showcase the virtues of their terroir. One is in fact reminded of restrictions already imposed or attempted by certain regional VDP chapters. But it must be noted that the VDP-Rheinhessen’s recent reinstatement of site-designated, residually sweet Kabinett and its tolerance for under-12% alcohol Grosse Gewächse (discussed as part of a lengthy earlier article that I published on this site) suggests if anything a (welcome!) trend nationwide toward renewed stylistic catholicity. So much then, for the likelihood that g.U.s alone will supply consumers with an increasingly clear notion of the sort of Riesling they are going to find in their glass.

When it comes to pruning back allowable vineyard names, the VDP has been hard at work. “We aren’t just in the process of building new classificatory levels, but are, to a large extent, concerned with renovating [sanieren] the existing floors,” says Löwenstein, “so, for instance, out of 650 site names on the Mosel, we have forbidden ca. 600 of them.” But even allowing for some hyperbole—at last count, there were 522 Einzellagen and 29 registered Gewannnamen in the greater Mosel, from among which the VDP recognizes 74 “classified vineyards”—as Lars Carlberg and I have pointed out, these numbers ignore at least four dozen historically and still demonstrably top-notch sites, ones that just don’t presently happen to be farmed by any VDP member. (Some of these were taxed at a higher rate under Prussian administration than were many current VDP “Grosse Lagen.”) And for every Mosel Einzellage that Löwenstein would argue is unworthy to form the basis of a future g.U., how many might there be that by his own criteria, like Uhlen, are worthy of generating multiple discrete g.U.s? For instance, the aforementioned tally of 74 “classified vineyards,” only counts Pündericher Marienburg once; but Clemens Busch—Löwenstein’s friend and a fellow VDP member since 2007—doesn’t just label wines “Marienburg” but recognizes and labels wines to reflect five topologically and geologically distinct, “sensorially confirmable” sites within that Einzellage.

And we have just now merely been imagining. How any of the scenarios just envisioned will be realized in practice is another and for now unanswerable question. Many growers supportive of the g.U. principle eloquently emphasize the need to take small steps in what they see as a positive direction. And as Dirk Richter has sought to caution us, small steps might well be the only possible kind, precisely because meaningful reorganization of German wine regulations as a whole will require extensive collaboration and consensus within and among winegrowing regions and winegrower organizations, as well as decisive federal impetus.

“I personally have absolutely no plans to register additional g.U.s in the future,” reports Schönleber. “Since it’s going to become easier to apply for g.U. status, their numbers will no doubt increase. Still, one hopes that impending changes in the Wine Law will render many such efforts unnecessary." Fürst expresses a similar sentiment: “We hope that in the end all [of our designated] vineyard sites will have the same [legal] status,” i.e., as g.U.s, “but for the moment we see no necessity to press ahead with [registering] the existing Bürgstadter Lagen. In my view, this is an issue that needs to be put in order at the federal level [bundesweit]. We hope that at some point things will be folded together into a unified system.” Do these hopes represent more than wishful thinking? Löwenstein professes “delight and pride” in having grasped the initiative “to take small steps [and] to have laid down a blueprint” that he believes should be applied throughout viticultural Germany if the system of EU law is to be properly implemented . Yet he also expresses resigned pessimism: “Given the balance of powers and state of consciousness [Kräfteverhältnis und Bewusstseinszustand] that currently prevail in the wine scene, I can’t really imagine such a consequential implementation taking place. But who knows. Perhaps at some point, when there is a new generation ....”

If the faith of optimists proves justified and a unified system can indeed be realized that involves either an elimination or an integration of the “old law’s” Einzellagen, Gewannnamen, and VDP-Lagen, this accomplishment will almost certainly involve a years-long period of transition during which, unfortunately, yet greater numbers of consumers are liable to become frustrated with or discouraged by the complications of German wine nomenclature. Meanwhile, many VDP members, including Fürst and Schönleber, express satisfaction with the classificatory and marketing structure that organization has built up over the years, years during which one must certainly grant the VDP leadership’s point that they would have been ill-spent waiting for reorganization on a federal level or wholesale revision of the existing German Wine Law. Fisch and Rayer conclude their rosy assessment of g.U.s with a plea for patience: “This will take time. But then, Rome wasn’t built in a day either.” Alas, the same could be said of Babel. And communication broke down there precisely once it was built.4 ♦

1German-speaking readers are encouraged to search for copies of Vinaria 02/2007, 01/2013, and 01/2015; English-speakers to consult The World of Fine Wine issues 47–48 (2015), as well as the current issue (number 62) and its successor. Unfortunately, my columns in those journals are only occasionally and selectively made available online by their publishers.

2In Austria, growers have generally rolled over and acquiesced to DACs highly restrictive in terms of which grape varieties they permit. The entire vast Weinviertel, for example, only has DAC status for Grüner Veltliner, so that wines rendered there from any other grape can only indicate the Land of Niederösterreich as their place of origin, which ranges from the edge of the Wachau to the westernmost vestiges of the Carpathians more than a hundred kilometers distant. Detailed comparisons with Austria would lead us too far into foreign territory. But it should be noted that Austria has only 13 DACs, with three additional ones imminent but only two or three more even being discussed. And while these range from 14,000 to just 300 hectares, nearly all of them are coextensive with long-standing regions, and, thus far at least, none of them is nested or geographically overlapping. (Update: There is now an exception. In 2020, the DAC Ruster Ausbruch was established solely for a restricted class of nobly sweet wines from certain grapes and grown in the commune of Rust, while dry white and red wines grown there can be labelling for the surrounding Leithaberg DAC.) Thus far, too, no Austrian grower has appealed to the EU for a “private” g.U., and the relevant regional committees would almost certainly frown on any such attempt. The vineyards of Austria, whose perimeters and names have recently been certified, follow with relatively few exceptions 19th-century cadastre entries and maps, and no layering or ambiguity such as that of German Gewanne within Einzellagen that may be similarly named is foreseeable. (There are Grosslagen. But these have undergone some welcome recent scrutiny and revision, along with a reduction in number.)

3I have argued extensively for what strikes me as the rather obvious conceptual separation of site and style – albeit, apparently without convincing those controlling the levers of wine legislation. In this regard, readers might seek-out not only my aforementioned columns in The World of Fine Wine, but also those in issues 49/2015 and 50/2015 under the rubric “Style and Typicity,” which attempt to explain in more detail why terroir-influence does not imply a shared taste profile, first with examples from the Greater Mosel (“No Czar for the Saar”) then from Austria’s Neusiedlersee (“Not rounding the corner”). Among my columns for Vinaria, see especially the already referenced issue 01/2013: “Stil und Lage.”

4Many thanks to Al Drinkle, whose question posed here on January 22 prompted me to embark on this exposition. Thanks to Lars Carlberg, Andreas Durst, and (once again) Al Drinkle for having inspired this last Babel analogy. All quotations whose sources are not otherwise cited represent translations from my [or "the author's] conversations or correspondence with the person quoted. For purposes of clarification, the italicized original German word or phrase employed is sometimes inserted in brackets.

- Posted in Articles, Vineyards

- | Tagged: David Schildknecht, Heymann-Löwenstein, VDP, vineyard classification, Winninger Uhlen

I can appreciate that Reinhard Löwenstein wants to make three separate bottlings of Uhlen based on soil type, but I don’t understand his stance that these designations and taste profiles are necessary if a producer wants to make a wine from Uhlen, much less his point of view on g.U. in general. Likewise, a producer of Uhlen—which was how the wines were designated during the Mosel’s heyday—should be able to blend grapes from different sections of this steep, terraced hillside and still be able to call it Uhlen. This is no different from Jean-Louis Chave blending his various parcels spread across the different soil types in Hermitage. It doesn’t have to be a separate Bessards bottling.

I also question Löwenstein’s justification in calling an area Blaufüsser Lay that doesn’t historically have this place-name on the cadastral map. As you point out in the piece, all three place-names with Blaufüsser Lay are in what is now called Laubach.

In contrast, Fürst and Emrich-Schönleber are less rigid in their views on g.U.s, and I can better relate to why they chose to go this route. It makes sense, especially in the case of Monziger Niederberg.

An article that’s so immense and punctilious without being the least bit verbose is a strong indicator of a convoluted topic. Maddeningly convoluted. Call me a pessimist, David, but I feel that insofar as German wine is concerned, your vision of an impenetrable and dizzying world is (as Löwenstein concedes) already a reality in the eyes not only of most wine drinkers, but also most professionals. (It’s probable that as a result of undue alienation, ambitious young sommeliers are more likely to be able to name the top three indigenous grapes of Serbia than to explain the differences between Grosslage, Grosse Lage and Erste Lage…). The gloomiest way of looking at this might be through the lens of apathy with the justification that none of this really matters as everybody is already sufficiently bewildered… what’s another layer of confusion?

Sadly, I’m only partly joking. You’ve written an incredibly comprehensive and horrifying piece and on behalf of all of us who are desperately trying to keep up, thank you for doing so. I’m presently trying to reconcile the idea that inevitably Germany will have to make adjustments in order to conform more heartedly to a EU-wide Wine Law with the fact that the first steps towards this seem to consist of little more than overdubbing a few rounds of indecipherable caterwauling atop an already cacophonic anthem.

One question – has the Mosel inaugurated Erste Lagen? You mentioned that Knebel is lobbying for Sternberg to be recognised as such.

Thanks again for writing this. No doubt that as things develop, this article will remain indispensable for its virtually exhaustive survey of the conceptual landscape.

Thanks for your kind comments, Al – not to mention for having been one of those who goaded me into writing this piece! (You might be the sole person other than Lars and myself who has read it through twice ;- )

I am only aware of at least a little renewed talk about the VDP-Mosel inaugurating Erste Lagen, not of any new consensus let-alone action. And if they were to inaugurate them, then (as I explained “VDP.Klassifixation”) short of downgrading existing Grosse Lagen (which is winepolitically unthinkable) there will likely end up being very few Mosel Erste Lagen. That’s because most VDP-Mosel member-vintners (notice I’m ceasing to write “growers,” Lars ;- ) aren’t effectively in a much different position classification-wise than that of their Rheinhessen counterparts, in that virtually any vineyard they consider worthy of label-mention has had Grosse Lage status conferred on it. (The only difference – as also explained in my piece about the VDP.Klassifixation – is that the VDP-Rheinhessen 1) classifies a large unnamed surface area as “Erste Lage” and 2) has an express provision whereby on request of a member, a specific site name can be approved by the full membership as designating an Erste Lage, which is how Keller obtained permission to mention Monsheimer Silberberg (which name, incidentally, he utilizes not for Riesling but for Rieslaner).

I don’t know where Knebel and the VDP stand in their discussions. He would I’m sure be happy to have Sternberg recognized as a Grosse Lage but (as I’m sure Löwenstein would argue) Uhlen and Röttgen may be viewed as being in a class of their own, hence the thought that Sternberg might be declared an Erste Lage. (I should have footnoted my mention of this possibility to forestall your obvious question.) But if Sternberg were to be so-recognized, then I would speculate (this is of course all speculative!) that this too would proceed along lines familiar from Rheinhessen, i.e. that Sternberg, like Keller’s Silberberg, would in effect represent an ad hoc exception to the rule put in place at the reasonable behest of a single member.

Incidentally I plan a follow-up piece in which I’ll argue systematically for those specific changes I think are realistic as well as sufficient to eliminate many of the worst ambiguities and contradictions in German wine regulation. (Hint: These will NOT include a vineyard classification ;- ).

Reinhard Löwenstein has long argued that only Uhlen and Röttgen are Grosse Lagen, but I find it hard to believe that the best parts of Hamm and Brückstück—in particular, Sternberg within the latter—are not worthy of this classification, or, at the very least, should be given some type of recognition, especially since the VDP Mosel doesn’t have Erste Lagen. It should be noted, too, that an original part of Hamm (Im oberen Hamm) is in the present-day Uhlen (Uhlen Blaufüsser Lay, to be exact), and the ur-Brückstück (a most impressive steep, terraced hillside) is in today’s Röttgen.